Tolkien Ensemble, Song of Durin, TE CD 2, Track 9, 6:41.

Howard Shore, Moria, LotR FotR CD 2, Track 12, 2:28.

Lord of the Rings Musical, Lament for Moria, LotR M, Track 8, 1:38.

Howard Shore, Moria, LotR FotR CD 2, Track 12, 2:28.

Lord of the Rings Musical, Lament for Moria, LotR M, Track 8, 1:38.

We have already touched on the unique way of the Dwarves in which they dealt with outsiders: Fervently guarding their customs and language, they composed special Westron versions of their songs, or completely new songs in Westron, as well as (presumably) instrumental music for interaction with other cultures. Some of those pieces are very old, for example the Song of Durin, which Gimli sings after Sam spoke of Moria as “darksome holes” (LotR, 315). The song speaks of Durin, one of the seven forefathers of the Dwarves, and arguably the most important of them. We do not know when the song was composed, but Gimli says that Durin is “still remembered in our songs”, which means that there are several songs and implies that the one he is about to sing is not of recent origin and widely known. Maybe it belongs to the songs intended for representation when dealing with customers. The song may be regularly sung at such occasions for guests to introduce them to Dwarven history. It contains a number of musical references, which are written bold in the following text:

The world was young, the mountains green,

No stain yet on the Moon was seen,

No words were laid on stream or stone

When Durin woke and walked alone.

He named the nameless hills and dells;

He drank from yet untasted wells;

He stooped and looked in Mirrormere,

And saw a crown of stars appear,

As gems upon a silver thread,

Above the shadows of his head.

The world was fair, the mountains tall,

In Elder Days before the fall

Of mighty kings in Nargothrond

And Gondolin, who now beyond

The Western Seas have passed away:

The world was fair in Durin's Day.

A king he was on carven throne

In many-pillared halls of stone

With golden roof and silver floor,

And runes of power upon the door.

The light of sun and star and moon

In shining lamps of crystal hewn

Undimmed by cloud or shade of night

There shone for ever fair and bright.

No stain yet on the Moon was seen,

No words were laid on stream or stone

When Durin woke and walked alone.

He named the nameless hills and dells;

He drank from yet untasted wells;

He stooped and looked in Mirrormere,

And saw a crown of stars appear,

As gems upon a silver thread,

Above the shadows of his head.

The world was fair, the mountains tall,

In Elder Days before the fall

Of mighty kings in Nargothrond

And Gondolin, who now beyond

The Western Seas have passed away:

The world was fair in Durin's Day.

A king he was on carven throne

In many-pillared halls of stone

With golden roof and silver floor,

And runes of power upon the door.

The light of sun and star and moon

In shining lamps of crystal hewn

Undimmed by cloud or shade of night

There shone for ever fair and bright.

There hammer on the anvil smote,

There chisel clove, and graver wrote;

There forged was blade, and bound was hilt;

The delver mined, the mason built.

There beryl, pearl, and opal pale,

And metal wrought like fishes' mail,

Buckler and corslet, axe and sword,

And shining spears were laid in hoard.

Unwearied then were Durin's folk;

Beneath the mountains music woke:

The harpers harped, the minstrels sang,

And at the gates the trumpets rang.

The world is grey, the mountains old,

The forge's fire is ashen-cold;

No harp is wrung, no hammer falls:

The darkness dwells in Durin's halls;

The shadow lies upon his tomb

In Moria, in Khazad-dûm.

But still the sunken stars appear

In dark and windless Mirrormere;

There lies his crown in water deep,

Till Durin wakes again from sleep.

(LotR, 315).

There chisel clove, and graver wrote;

There forged was blade, and bound was hilt;

The delver mined, the mason built.

There beryl, pearl, and opal pale,

And metal wrought like fishes' mail,

Buckler and corslet, axe and sword,

And shining spears were laid in hoard.

Unwearied then were Durin's folk;

Beneath the mountains music woke:

The harpers harped, the minstrels sang,

And at the gates the trumpets rang.

The world is grey, the mountains old,

The forge's fire is ashen-cold;

No harp is wrung, no hammer falls:

The darkness dwells in Durin's halls;

The shadow lies upon his tomb

In Moria, in Khazad-dûm.

But still the sunken stars appear

In dark and windless Mirrormere;

There lies his crown in water deep,

Till Durin wakes again from sleep.

(LotR, 315).

Not only can we learn from this song a lot about the appearance of Khazad-dûm in its early days after its foundation by Durin (the name Moria was later given to the place by the Elves), but also about the culture of the Dwarves who lived there. We learn of "golden roof and silver floor" and of "shining lamps of crystal". All this conjures up the image of a grand and very bright culture under the mountain - notably different from the way the place appears in the Third Age. We also hear of harps, minstrels singing and trumpets. The latter sound at the gates, which again suggests they are used for communication or to greet people approaching or leaving Khazad-dûm. It is no surprise that harps are mentioned - Thorin's magnificent harp is testament of the importance of the instrument to the Dwarves. The mention of minstrels is notable, however, because it confirms that Dwarves had professional singers, not just instrumentalists. For our purpose this means that vocal performances, either soloist or accompanied by instruments, have a high value in Dwarven society; otherwise minstrels would not be mentioned in such a song. It also means that songs, or vocal performances in general, were not just part of popular culture, but also performed at official events. Again: With the guardedness of the Dwarves, they would not mention minstrels in a song addressed to a non-Dwarvish audience unless everyone would know of their existence when visiting one of their dwellings. Gimli clearly sings the song for the Fellowship to hear - specifically for Sam, who in a way insulted the memory of Khazad-dûm - to inform them of former times, so his choice of this particular song was certainly deliberate. The Song of Durin therefore most likely is one of the hallmark songs to sing to outsiders and as such has to be taken as the epitome of representative music.

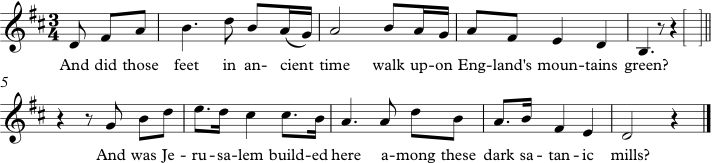

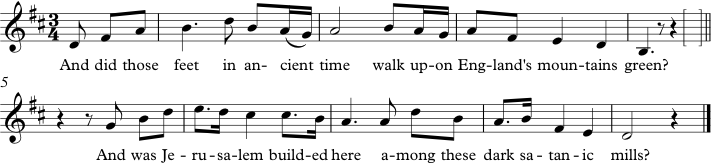

So what did the Tolkien Ensemble make out of this song? Of all pieces by the Ensemble, the Song of Durin stylistically stands out the most. While most of the other renditions by the Ensemble are not directly modelled after a particular style, the Song of Durin certainly is. Stylistically, it is heavily oriented on 19th and early 20th century late romanticist tonal language, very similar to Edward Elgar and Ralph Vaughan Williams. In fact, there is a striking similarity to sacred orchestral music from this period. We can find big similarities with Edward Elgar’s orchestral arrangement of Hubert Hastings Parry’s setting of the poem And did those feet in ancient time, written by Williams Blake. This hymn, which today is mostly known as Jerusalem, along with other stylistically similar pieces from traditional English music can be regarded as a big inspiration for the Tolkien Ensemble’s version of the Song of Durin. It shall be noted, however, that composer Peter Hall denies drawing any inspiration from Jerusalem specifically. Nevertheless, this hymn remains the best example to illustrate the stylistic similarities, so we will have a look at the melody of both Jerusalem and the Song of Durin:

Hubert Hastings Parry: Jerusalem (excerpt).

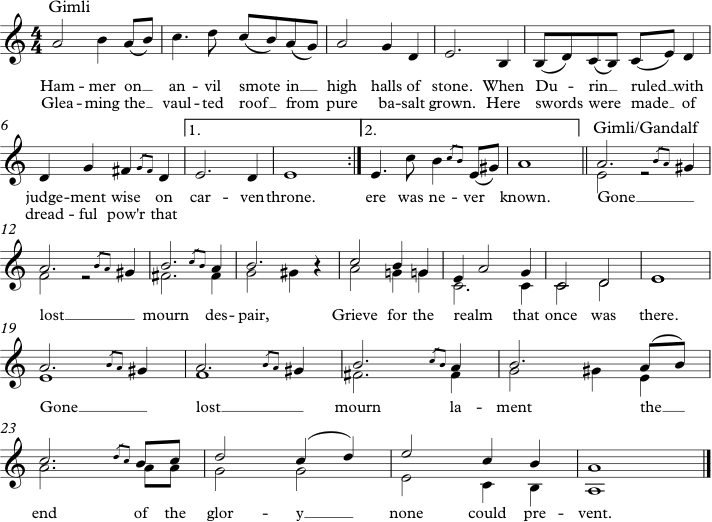

transcription (excerpt): Song of Durin, TE CD 2, Track 2.

http://soundcloud.com/middle-earth-music/4-1-4-song-of-durin-2nd-stanza/s-b4AIp

The pieces share the same key signature as well as time signature and are performed at roughly the same speed. The general shape of the melody is diametrically opposed – while Jerusalem first moves up, the Song of Durin moves down. Later on this is reversed. We may see in this an image of the subject matter: While Jerusalem is about Christ supposedly having set foot on the British Isles (an apocryphal story, which is not considered canon, but is widely known and accepted on the British Isles) and such describes the lifting of the country to a higher state of being, only to question this act by referring to the “satanic mills” of the Industrial Revolution, the Song of Durin indirectly deals with Durin first going down into the mountains when founding Khazad-dûm, but then bringing the dwelling to fame – moving it up, one may say.

Large orchestra accompanies both pieces, with the Song of Durin bringing the brass in the foreground and mixing the strings more to the background as a pad. This supposedly is to differentiate Dwarven music from Elvish music. Indeed, the song mentions trumpets and harps, so brass instruments seem more fitting to a Dwarven hymn. In the middle of the Song of Durin, there is a percussive B-part (3:30), which has no counterpart in Jerusalem. This part with a steady anvil beat (3:44) most likely represents the craftsmanship of the Dwarves and the work of Durin’s folk, or Longbeards as they called themselves during the founding of Moria and after.

http://soundcloud.com/middle-earth-music/4-1-4-song-of-durin-percussive/s-nbP14

This part is followed by the last verse (4:15), which brings the piece to present time and mourns the loss of the splendour of the old days.

http://soundcloud.com/middle-earth-music/4-1-4-song-of-durin-last/s-hMg6i

Caspar Reiff, who wrote the arrangement to the melody written by Peter Hall, confirms the music of Elgar being an inspiration for the Song of Durin:

The Song of Dúrin [sic!] calls for grandeur. Peter Hall made the melody and asked me to do an "Elgarian arrangement". I had a look on the score of Elgar’s first Symphony in A Flat Major, Op. 55 - and pretty much did the same as Elgar in the arrangement.

Reiff, e-mail 2

If we consider Tolkien’s goal to create a mythology for the English with his works and think of the craftsmanship that went into the great English cathedrals (Ely Cathedral, the “ship of the fens”, comes to mind) as well as the importance of the style of Elgar and his contemporaries for English music, choosing a style modelled after English sacred music fits very well into Tolkien’s plan. The Dwarves represent craftsmanship, ambition and in a way, through their many dealings with other cultures as builders and merchants, are a counterpart to the British Empire – but without its darker sides, as it seems. During The Lord of the Rings many places built by Dwarves are mentioned, so they appear to have had a monopoly on stonework, or at least were the most talented craftsmen in Middle-earth. Mithril seemed to be under their sole control, and with the exception of the tunnels deep beneath Moria (which, according to Gandalf, were carved by “nameless creatures”)13, they also are the only race extensively building structures beneath the surface. We can hardly count Hobbit holes in this category since these are set into hills and do not have multiple storeys.

The Ensemble’s version of the Song, with its use of late romanticist English sacred music, uses the style to evoke the picture of the Dwarven race as noble, ancient and very high-cultured professional craftsmen with a great sense of tradition and honour, proud of their history and longing to make their culture shine again like it did in their glory days. In this way their way of thinking is different from the Elves’: These maintain that their time is gone after the Third Age and leave. Their songs speak of the West and of former times, but never with the aim of bringing back those days, only to remember them as a thing long since gone, never to return. The Dwarves think the other way and want to still do great tasks. They are also eager and ready to seize new opportunities to create works surpassing even their greatest deeds of old: When Gimli encounters the Glittering Caves of Aglarond, he describes it as something “such as the mind of Durin could scarce have imagined in his sleep” (LotR, 547). He contradicts Legolas, who does not all like the thought of hordes of Dwarves marching into the caves and marring everything, and refers to Durin’s days:

None of Durin’s race would mine those caves for stone or ore, not if diamonds or gold could be got there. [. . .] We would tend those glades of flowering stone, not quarry them. [. . .] a small chip of rock and no more, perhaps, in a whole anxious day [. . .] We should make lights, such lamps as once shone in Khazad-dûm [. . .].

LotR, 548

These lamps seem to be a special achievement for the Dwarves; not only does Gimli extensively describe the way in which his people would bring light into the dark halls, but also does the Song of Durin refer to these lamps. Again it is obvious to point out the similarities to the art of architecture, where light is an important factor to consider. This very much rings true also for cathedrals, which use light to increase the perception of depth and to highlight important parts of the building. Lastly, Dwarves lay much importance on tradition, a trait they share with most religions. After considering all these facts, choosing a style very similar to late-romanticist (orchestral) sacred music for this culture makes sense and by its connotations gives the Song of Durin another layer of meaning – one that arguably fits with Tolkien’s ideas.

The motion picture, on the other hand, concerns itself more with the current state of Khazad-dûm. The back-story of how the place came to be as well as Gimli’s song itself are not present in the film. This material was probably cut because it did not contribute anything important to the actual story – from a dramatic point of view, in the film the whole Moria sequence basically only serves to show the beginning dissolution of the Fellowship: The characters debate about whether to take this way at all after failing at the Caradhras, with the decision ultimately lying with Frodo, foreshadowing the breaking of the Fellowship later when he and Sam depart for Mordor alone. Gandalf fights Durin’s Bane (the Balrog) and dies, only to be sent back later because his mission was not yet fulfilled. But even though the Song of Durin, as it is presented in the book, is left out of the motion picture, the film nevertheless has its own Song of Durin. Dubbed Durin’s Song by Adams, it is sung by male voices while the Fellowship wanders through the depths of the Dwarrowdelf. The song is written and sung in Neo-Khuzdûl14 and its content as such is not accessible to the audience. It is here given in English:

Durin who is Deathless 15

Eldest of all Fathers

Who awoke

To darkness

Beneath the mountain

Who walked alone

Through halls of stone

(Adams, 176).

Eldest of all Fathers

Who awoke

To darkness

Beneath the mountain

Who walked alone

Through halls of stone

(Adams, 176).

Durin who is Deathless

Lord of Khazad-dûm

Who cleaved

The dark

And broke

The Silence

This is your light!

This is your word!

This is your glory!

The Dwarrowdelf of Khazad-dûm!

Lord of Khazad-dûm

Who cleaved

The dark

And broke

The Silence

This is your light!

This is your word!

This is your glory!

The Dwarrowdelf of Khazad-dûm!

As we can see, the text is noticeably different from Tolkien’s text and only introduces Durin and his awakening as well as detailing the importance of Khazad-dûm. The audience is never told of this as the song is only translated in Adam’s liner notes for the complete recordings. For information about the musical features and the intention of the song in the film, we will draw upon Adams himself:

Shore’s music rumbles muscularly but distantly, low strings and male voices gathering like a brewing storm over steady pacing in percussion. These are the tones of the Dwarves, a music of edges and corners, hewn stone and etched rock. A ghostly chorus sings for all those who lost their voices in the Dwarves’ ruined deeps [. . .] MORIA’s music is among the most cheerless in Fellowship’s score.

Adams, 176

This use of a song about Durin is diametrically opposed to the way the song works in the book and is one example where elements need to be changed when transferring a book to the silver screen. The tonal language of “Shore’s Dwarves” is built around the present day situation of Moria – apart from the fact that there obviously are no Dwarves around to sing the song, this presents a logic fallacy: The Dwarves do not know about the nature of the evil that has befallen the Dwarrowdelf, because no one has ever seen the Balrog and lived to tell the tale. Even Gandalf expresses his hope that there may still be Dwarves in Moria and Gimli is eager to go there. It is likely that Gandalf has some inkling as to what may be waiting in the deep (after all he is a Maiar himself and very familiar with Balrogs, which are Maiar, too), but he does not express his thoughts and Gimli clearly is very much surprised to find out about the nature of Balin’s death. King Thrain, who after retaking Moria earlier warned of what lies waiting there, does not seem to have realised that it was a Balrog. So there are no songs mourning “those who lost their voices”, as no one knows of their fate. We can assume that Shore did not envision all Dwarven music to mourn fallen comrades or to speak of other terrible events. Unfortunately, there is no other music of Dwarvish origin in the film, so we do not know how the filmmakers would have imagined Dwarven music for happy events to sound like.

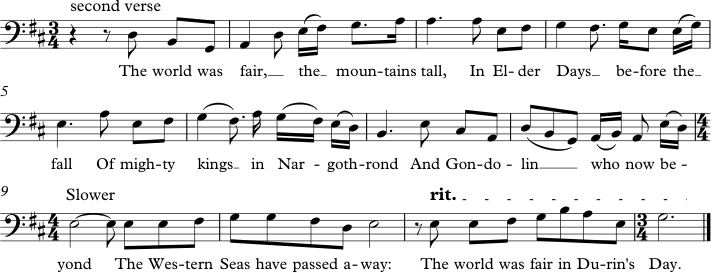

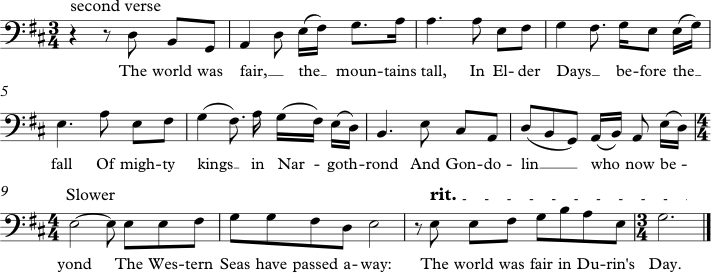

The stage version of The Lord of the Rings also has a song that deals with the former glory of Moria, called Lament for Moria. The mere presence of such a song is interesting to note: Given the time constraints of a stage show, cutting a description of a member of a race that has no important part of the plot at all seems like a logical conclusion. But again we can observe the principle at work on which the creators based their decisions: To stay true to Tolkien’s vision without feeling compelled to take everything into the show in its original wording. The culture of the Dwarves clearly was important to Tolkien. Not only does Gimli tell us a lot about his race with the Song of Durin, but we also get a lot of information about the Dwarves’ mind-set with his musings about the Glittering Caves of Aglarond and numerous other insights about Dwarven culture.

The state Khazad-dûm is in at the time of the book is presented as a result of both the destructions by the Balrog as well as by plunderings and the use of the place by Orcs. Dwarves did not live in “darksome holes”, as the author takes great care to assure us. We can assume that the creators of the stage musical realised this and therefore decided to devote an entire musical number to the topic, not just a side note, not to speak leaving it out completely.

Once again the original text by Tolkien is not used, but a new text is created, drawing on Gimli’s song with a duet by Gimli and Gandalf. This suggests that the song sung by the two is well known in the universe of the stage show, similarly to its status as a representative song in the book; otherwise Gandalf would not have been able to join in.

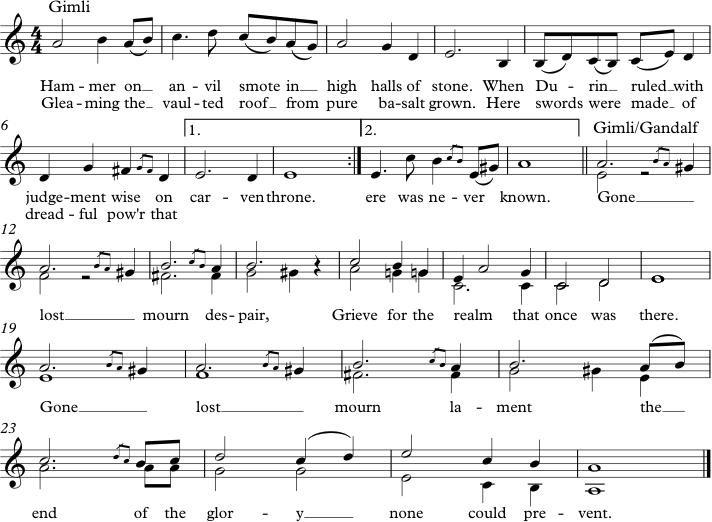

transcription (excerpt): Lament for Moria, LotR M, Track 8.

Apart from the fact that Gimli here is suddenly a tenor and therefore does not at all “chant in a deep voice” (LotR, 315), the meaning of the song follows the book quite closely. Gimli was probably made a tenor due to the fact that Gandalf and Saruman are basses. Like the Song of Durin from the book, the Lament deals with the former times and laments their passing, contrary to the motion picture, which laments the fallen Dwarves and therefore shifts the focus away from a display of Dwarven culture to an underscoring of the current situation in the plot. The Lament itself is a slow, hymn-like song, very sad and melancholic, but not pessimistic. It merely states the facts, but does not try to alter anything. On the contrary: It is expressly mentioned that no one could have prevented the things that happened. This suggests that maybe in the musical the Dwarves saw what happened as an accident. As they did not know of the Balrog, this is likely and would explain the making of such songs as a form of remembering the past. Just as the song in the book, here the Lament serves as a means to inform the reader/spectator of the background of the culture Gimli belongs to – with only the literally “darksome holes” of Moria infested by Orcs present, it is important to show the recipient the way the place would be like in better times.