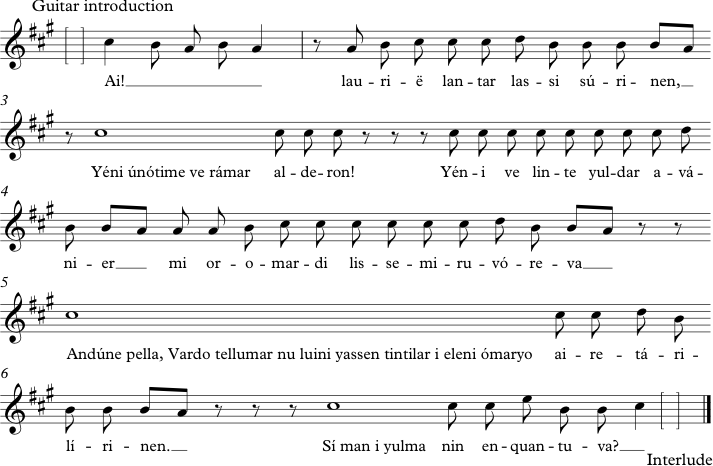

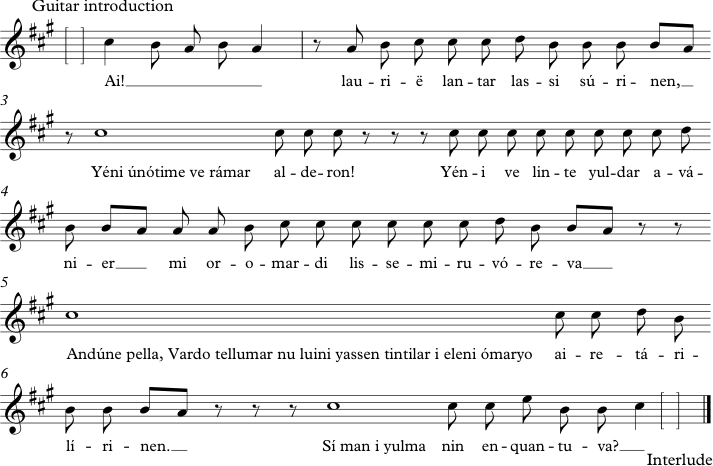

Donald Swann, Namárië, Swann, 22.

Tolkien Ensemble, Song Of The Elves Beyond The Sea / Galadriel's Song Of Eldamar (II), TE CD 2, Track 13, 6:13.

Tolkien Ensemble, Song Of The Elves Beyond The Sea / Galadriel's Song Of Eldamar (II), TE CD 2, Track 13, 6:13.

For a world so full of music and musical allusions, we have precious little first-hand information about how Tolkien imagined this music to sound like. There is one exception, though, where we not only have a description of the general stylistic qualities of a piece, but even a melody that goes with it by hand of the author. Galadriel sings Namárië after the Fellowship leaves her realm. The song is the longest Quenya text in the book. It deals with “things little known on Middle-earth” (LotR, 377) and refers to the Undying Lands and Galadriel’s desire to return there, something that was forbidden to her due to her being part of the group of Elves that went to Middle-earth against the wish of the Valar. More about this topic can be found at 4.1.11 and 4.2.4. In the song she expresses the wish that Frodo may find the way to the Undying Lands; and indeed he ultimately does and even Galadriel is granted to go there, too, presumably because of her aid during the War of the Ring.

Donald Swann, who first set the poem to music, maintains that while Tolkien liked the rest of his renditions, he “bridled at my [Swann’s] music for “Namárië.” He had heard it differently in his mind, he said, and hummed a Gregorian chant.” (Swann, vi). So this song is the only music directly confirmed by Tolkien. Swann therefore to use Tolkien’s melody for the song and just print it in the way the author had told him, so technically speaking, Namárië is composed by Tolkien, not Swann.

Sadly, Swann’s original version of the song seems to be lost; of all the research done for this paper, this was the only avenue that went dry.

excerpt: Namárië, Swann, 22.

Save for the introduction, the interlude and the ending of the piece, Namárië is performed unaccompanied; the tempo is given as “freely”. Giving the Elves a musical language oriented towards plainsong makes sense if one sees them as the oldest, most traditional race. Naturally, if the author himself asserts that this music sounded like plainsong, he is bound to be right.11

Nevertheless, if we think of the idea of “reverse progress”, it seems curious for such an ancient and important piece of music to be quite so simple. We would expect rather rich polyphony in High Elven music, as it is nearest to the First Music. One possible explanation would be that Galadriel simply preferred this mode of singing. Also if she only ever sang her lament to herself, there would have been no other musicians present for a polyphonic version. It is likely that Tolkien chose the plainsong approach to represent Galadriel’s loneliness: Far away from home, with no prospect to go back and the knowledge that when the Master Ring would be destroyed, her time to fade would come, too, due to her Ring loosing its power. So the most likely explanation for Tolkien’s wish to see this song represented as plainsong is that he intended it as a representation of Galadriel’s personality, not as a model of what High Elven music sounded like in general.

We need to leave it at this and see Namárië as what it is: The only music from Middle-earth passed on to us by Tolkien himself, which may or may not tell us more about the musical taste of the author than of its singer. With this paper firmly building on the notion of “reverse progress” and assuming a very high level of musical culture throughout the whole of Arda, Namárië stands here as the only primary source of music available to us and most likely represents a single instance of Elvish music, not the norm.

The Tolkien Ensemble has also set this poem to music as the Song Of The Elves Beyond The Sea / Galadriel's Song Of Eldamar (II). The rendition at the first glance does not use a Gregorian chant, but instead is oriented towards operatic music, similarly to the other renditions of Elvish songs by the Ensemble. As we will see, though, it intelligently unites classical elements with plainsong technique, following Tolkien’s conception of Elvish music, yet at the same time removing it from being purely based on existing “real-world” musical styles.

The piece begins with a tremolo marimba introduction, with a female soloist providing figures on “aah”. The voice in the whole piece constitutes a major source of momentum, driving the piece forward. Midway through the introduction, an arpeggiated marimba pattern is taken over by the harp. Low male voices and a string section provide a pad. The actual poem begins at 0:53:

We need to leave it at this and see Namárië as what it is: The only music from Middle-earth passed on to us by Tolkien himself, which may or may not tell us more about the musical taste of the author than of its singer. With this paper firmly building on the notion of “reverse progress” and assuming a very high level of musical culture throughout the whole of Arda, Namárië stands here as the only primary source of music available to us and most likely represents a single instance of Elvish music, not the norm.

The Tolkien Ensemble has also set this poem to music as the Song Of The Elves Beyond The Sea / Galadriel's Song Of Eldamar (II). The rendition at the first glance does not use a Gregorian chant, but instead is oriented towards operatic music, similarly to the other renditions of Elvish songs by the Ensemble. As we will see, though, it intelligently unites classical elements with plainsong technique, following Tolkien’s conception of Elvish music, yet at the same time removing it from being purely based on existing “real-world” musical styles.

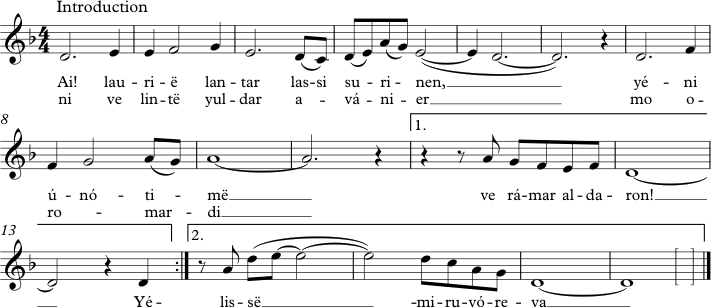

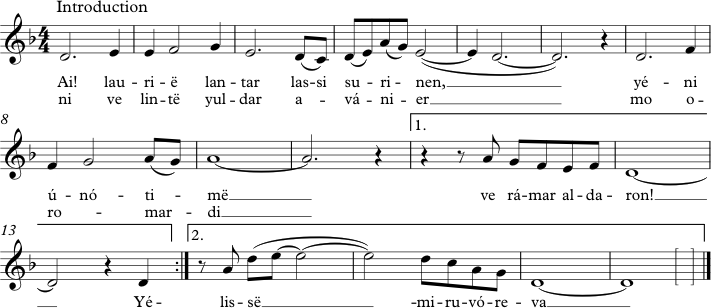

The piece begins with a tremolo marimba introduction, with a female soloist providing figures on “aah”. The voice in the whole piece constitutes a major source of momentum, driving the piece forward. Midway through the introduction, an arpeggiated marimba pattern is taken over by the harp. Low male voices and a string section provide a pad. The actual poem begins at 0:53:

transcription (excerpt): Song Of The Elves Beyond The Sea / Galadriel's Song Of Eldamar (II), TE CD 2, Track 13.

http://soundcloud.com/middle-earth-music/4-1-1-nam-ri/s-6p7AIDuring the whole piece, the string and choir pad stays consistent; the harp plays its arpeggiated eights pattern with the first beat silent. Only occasionally for added impact, the accompaniment stays silent for a number of beats at the end of lines as well as mid-piece for single lines. These sparsely used passages of unaccompanied soloist singing strongly evoke a feeling of plainsong, thereby establishing a link between the Ensemble’s mental image of what Elvish music sounds like (“something between folk music and classical music”, according to Caspar Reiff; Reiff, e-mail 2) and what we know of Tolkien’s ideas of Elvish music from Swann’s song cycle. It may be argued that the Ensemble’s approach of mixing learned classical music (including use of crafted instruments as a result of centuries of refinement of instrument families, establishing and suggesting an active development of instrument craftsmanship) with plainsong as described by Tolkien actually makes perfect sense by combining the author’s vision of the sound of Elvish music with the background of a musical style developed over centuries and rooted in firm harmonic and melodic rules, thus complying to the idea of all music in Middle-earth directly being derived and based on the First Music.

The Ensemble chose to record the version of the poem translated into English (or Westron) only as narration, making an analysis of this version for the purpose of finding possible ways in which the Elves adapted their songs to Westron-speaking audiences futile. We will, however, have the chance to look at a similar topic in the analysis of the Song of Durin (see 4.1.4).