Tolkien Ensemble, Elven Hymn to Elbereth Gilthoniel (I), TE CD 1, Track 5, 5:32.

Tolkien Ensemble, Elven Hymn to Elbereth Gilthoniel (II), TE CD 2, Track 3, 2:10.

Tolkien Ensemble, Elven Hymn to Elbereth Gilthoniel (III), TE CD 4, Track 17, 6:07.

Tolkien Ensemble, Sam’s Invocation of the Elven Hymn to Elbereth Gilthoniel, TE CD 3, Track 17, 1:33.

Donald Swann, I Sit Beside The Fire, Swann, 29-30.

Tolkien Ensemble, Elven Hymn to Elbereth Gilthoniel (II), TE CD 2, Track 3, 2:10.

Tolkien Ensemble, Elven Hymn to Elbereth Gilthoniel (III), TE CD 4, Track 17, 6:07.

Tolkien Ensemble, Sam’s Invocation of the Elven Hymn to Elbereth Gilthoniel, TE CD 3, Track 17, 1:33.

Donald Swann, I Sit Beside The Fire, Swann, 29-30.

The Hymn to Elbereth Gilthoniel is heard a number of times in the book: In the Fellowship of the Ring, the company hear Elves singing it after the Hobbits sang the Walking Song. The Elves sing it in Sindarin, but in the book the text is given in Westron (English),”as Frodo heard it” (LotR, 79):

Snow-white! Snow-white, O Lady clear!

O Queen beyond the Western Seas!

O Light to us that wander here

Amid the world of woven trees!

Gilthoniel! O Elbereth!

Clear are thy eyes and bright thy breath,

Snow-white! Snow-white! We sing to thee

In a far land beyond the Sea.

O Queen beyond the Western Seas!

O Light to us that wander here

Amid the world of woven trees!

Gilthoniel! O Elbereth!

Clear are thy eyes and bright thy breath,

Snow-white! Snow-white! We sing to thee

In a far land beyond the Sea.

O stars that in the Sunless Year

With shining hand by her were sown,

In windy fields now bright and clear

We see your silver blossom blown !

O Elbereth! Gilthoniel!

We still remember, we who dwell

In this far land beneath the trees,

Thy starlight on the Western Seas.

(LotR, 79).

With shining hand by her were sown,

In windy fields now bright and clear

We see your silver blossom blown !

O Elbereth! Gilthoniel!

We still remember, we who dwell

In this far land beneath the trees,

Thy starlight on the Western Seas.

(LotR, 79).

The hymn refers to the Vala Varda, who had, among many other names, been given the title “Elbereth Gilthoniel” by the Elves. Her role in Middle-earth can best be described as a goddess of light, though there is nothing that suggests her actively taking part in the physical world. In The Lord of the Rings she is of some importance not only in her function within the larger cultural and religious framework, but also because her invocation serves as a powerful weapon against the dark forces: When the Hobbits and Strider are attacked on top of Weathertop by the Nazgûl, Frodo exclaims “O Elbereth! Gilthoniel!” (LotR, 195). According to Aragorn, “More deadly to him [the Nazgûl] was the name of Elbereth.” (LotR, 198). Sam also calls her name when battling Shelob.

The Hymn being the first Elvish poetry heard by the Hobbits marks not only the importance of this particular piece, but also the importance of music in general in the context of different cultures meeting. Peter Wilkin remarks that “The first encounters between mortals and Elves that occur in The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings and The Silmarillion are all initiated by the hearing of poetry and music.” (Wilkin, 48).

The Tolkien Ensemble has set all the versions of the poem to music, including Sam’s invocation of Elbereth. Similar to the other songs with multiple versions, the different versions are numbered. The Elven Hymn To Elbereth Gilthoniel (I), whose circumstances are described above, begins with a heavily reverberated violin solo preceded by orchestral chimes. Double bass and a guitar come in (0:17), the latter clearly associated with High-Elvish harp music by being played in a very harp-like, plucked style. The violin plays long melodic arches over the steady arpeggiated pattern of the guitar with the double bass providing sustained bass notes. A solo singer sings the four stanzas of the hymn (from 0:57), with the third stanza separated from the second by a violin interlude (2:31-3:13). The text is unchanged, only in the second and fourth stanzas the first exclamation (Gilthoniel! / O Elbereth!) is repeated to make the text fit better to the melody.

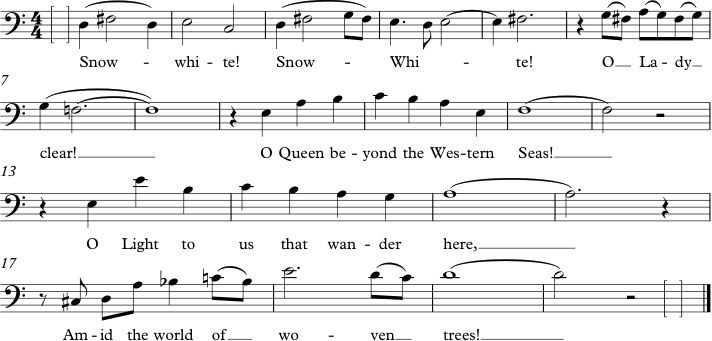

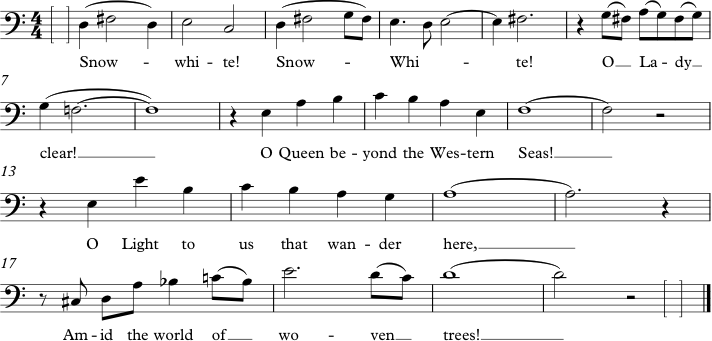

transcription (excerpt): Elven Hymn to Elbereth Gilthoniel (I), TE CD 1, Track 5.

http://soundcloud.com/middle-earth-music/4-1-7-elven-hymn-to-elbereth/s-9ej38

The second time the hymn is sung is in Rivendell: After Bilbo presented his poem about Eärendil the Mariner (see 4.1.3) and Frodo and Bilbo leave for some quiet place to talk, “a single clear voice rose in song” (LotR, 238). This version is sung in Sindarin and is the longest coherent text in the novel.

A Elbereth Gilthoniel

silivren penna míriel

o menel aglar elenath!

Na-chaered palan-díriel

o galadhremmin ennorath,

Fanuilos, le linnathon

nef aear, sí nef aearon!

(LotR, 238).

The Elves in Rivendell seem to have had solo singers. We do not learn who the singer is, presumably not Elrond and certainly not Arwen, as the latter is speaking with Aragorn at that time, but it is likely that Elrond had minstrels that sang these songs upon his request. After all, this is a song to maybe the most important Vala, so undoubtedly professional singers would have been employed. Like in the book, the Ensemble’s version, Elven Hymn to Elbereth Gilthoniel (II), is monophonic and unaccompanied. Sung by a solo soprano with heavy reverberation it is very much reminiscent of plainsong, stylistically similar to Namárië (see 4.1.1).

http://soundcloud.com/middle-earth-music/4-1-7-elven-hymn-to-elbereth-1/s-WZYsM

As mentioned earlier when looking at the Walking Song (see 4.1.6), when Frodo has finished his verse, Elves can be heard singing the hymn to Elbereth. This version, called Elven Hymn to Elbereth Gilthoniel (III) on the recording by the Tolkien Ensemble, seamlessly follows the Walking Song and stylistically is very different from any of the previous renditions: Over the whole piece, a mixed choir hums sustained chords over the solo singer singing the verses, with the words sung melismatically over very long arches. Despite the briefness of the poem, the rendition takes about six minutes. After the solo soprano has sung the first four lines of the poem (2:22), they are repeated with her being backed by part of the choir in unison. The next two lines are sung by part of the choir in unison with the soloist singing the first line of the poem repeatedly (4:40). The melodic phrase sung by the soloist is identical to the beginning of Galadriel’s Song of Eldamar (see 4.1.11). The last line of the poem is sung repeatedly by the soloist, while the choir repeats “beneath the trees”.

http://soundcloud.com/middle-earth-music/4-1-7-elven-hymn-to-elbereth-2/s-eHlQg

Sam’s Invocation of the Elven Hymn to Elbereth Gilthoniel was clearly recorded as a highly stylised version of the events. The book describes Sam’s invocation very differently from the rendition by the Ensemble: The song begins with a choir of Elves chanting “Gilthoniel A Elbereth!” corresponding to the “music of the Elves as it came through his sleep in the Hall of Fire in the house of Elrond” (LotR, 729). Then Sam sings the remainder of the song to a plucked guitar accompaniment in a very relaxed and laid-down manner (0:20) – exactly the opposite of the description in the book, where “his tongue was loosed and his voice cried in a language which he did not know”. Midway through his verse, a soprano soloist comes in, probably signifying the help of Elbereth (0:48). The rendition by the Ensemble best fits an operatic performance of the events, but falls short as a literal representation.

http://soundcloud.com/middle-earth-music/4-1-7-sams-invocation-of-the/s-jiWAB

Donald Swann in his song cycle has set the poem to music as part of I sit beside the fire (see 4.2.5). In its musical properties it very much resembles English folk music and does not appear to specifically make any concessions to what may be described as “Elvish” musical properties. In fact, the hymn uses the same melody as the titular song of the cycle, The Road Goes Ever On (Swann 1). The hymn is accompanied by guitar and modulates from D major to Eb major. Why Swann chose to include the hymn as a part in this song and did not follow the book setting it after the Walking Song, we can only guess. In fact, he did not set the Walking Song to music at all. According to him, combining the two songs “felt was not improper” to Tolkien himself (Swann, vii), but there is no further information given. The use of the melody of the first song of the cycle for the hymn likewise does not appear to be logical and again there is no information to be found about the reasons.